Key points

- Long-term management of chronic non-cancer pain should take a multidisciplinary approach that minimises use of opioid medicines.

- Effective pain management requires a strong, continuous, therapeutic relationship between doctor and patient.

- Active self-management strategies can build patient confidence that chronic non-cancer pain can be managed without an opioid medicine.

- Although chronic pain is a complex and challenging area to manage, GPs and patients should be aware of the effective non-pharmacological therapies available to support them.

- Non-pharmacological therapies can produce improvements in pain and function that are similar to those of opioid medicines, without the harm.

Download and print

If not opioids, then what?

Available evidence does little to support the use of opioid medicines for long-term management of chronic non-cancer pain. Clinical guidance currently recommends a multidisciplinary approach with an emphasis on non-pharmacological strategies and active self-management as the preferred method to improve function and quality of life.2

But how do GPs motivate their patients to become active participants in their own non-pharmacological pain management plans?

And what are some examples of non-pharmacological therapies that are available for people living with chronic non-cancer pain?

The limited role of opioids

Current clinical guidelines do not recommend the use of opioids in long-term chronic non-cancer pain management.3-5

Available evidence examining long-term (> 1 year) opioid efficacy and risk remains insufficient to determine the effectiveness of this therapy for improving chronic pain and function.6

In a recent meta-analysis of 96 RCTs involving over 26,000 patients with chronic non-cancer pain, treatment with opioids did not provide clinically important improvements in pain or function when compared with placebo.7 Although statistically significant, these improvements were less than the minimally important difference identified for either measure. They reduced pain by –0.69 cm on a 10 cm visual analogue pain scale (where a minimally important difference = 1 cm) and improved physical functioning by 2.04 points on the 100 point 36-item Short Form Survey physical component score (where a minimally important difference = 5 points).7

Opioids were associated with less pain relief during longer trials, which may be a result of opioid tolerance or opioid-induced hyperalgesia. The authors suggested that a reduced association with benefit over time might lead to prescription of higher opioid doses and consequent harms.7

In contrast, evidence on opioid-related harm continues to expand, with studies suggesting that higher opioid doses are associated with increased risk of harm.6,8

The harm associated with long-term opioid therapy is becoming more widely understood and includes; overdose, misuse, falls, fractures, myocardial infarction, endocrine effects, cognitive impairment and gastrointestinal problems.6,8 Opioid effects on the endocrine system include opioid-induced androgen deficiency (hypogonadism) and associated problems of sexual dysfunction and infertility.9

At any stage in the opioid prescribing journey, it's important for prescribers to recognise and discuss with their patients both the limited role of opioid therapy in chronic non-cancer pain, and the potential for serious harm over the long term.4 These are particularly important topics when starting conversations about reducing or stopping opioids .

From pain cure to pain management

The basis for effective pain management is a strong, continuous, therapeutic relationship between doctor and patient.4 Providing information and reassurance in a supportive environment enables patients to engage in shared decisions about their treatment goals. It should be acknowledged that a trusting, therapeutic relationship takes time and effort to build, and that this can be costly for patients in terms of time, financial burden and emotional effort.

A useful approach to communicating effectively within the therapeutic relationship is to change the paradigm from ‘pain cure’ to ‘pain management’. Consider discussing the difference between acute and chronic pain, to explain why standard acute pain treatments ie, opioid analgesics, fail to treat chronic pain.5

As patients begin to understand and accept this shift in treatment focus, GPs can encourage them towards active self-management techniques. These include strategies learned from:

- a cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) perspective – such as setting realistic goals, pacing activities and challenging unhelpful thoughts

- acceptance- and mindfulness-based interventions

- physical therapies that aim to gradually improve function despite persisting pain.3,5

Addressing each individual’s pain condition from a biopsychosocial perspective and assessing how pain affects their life can also help to consolidate their understanding that the goals of pain management should go beyond pain relief alone.4 Examples of goals include increased activity, improved physical function, and improved social, emotional and mental health.

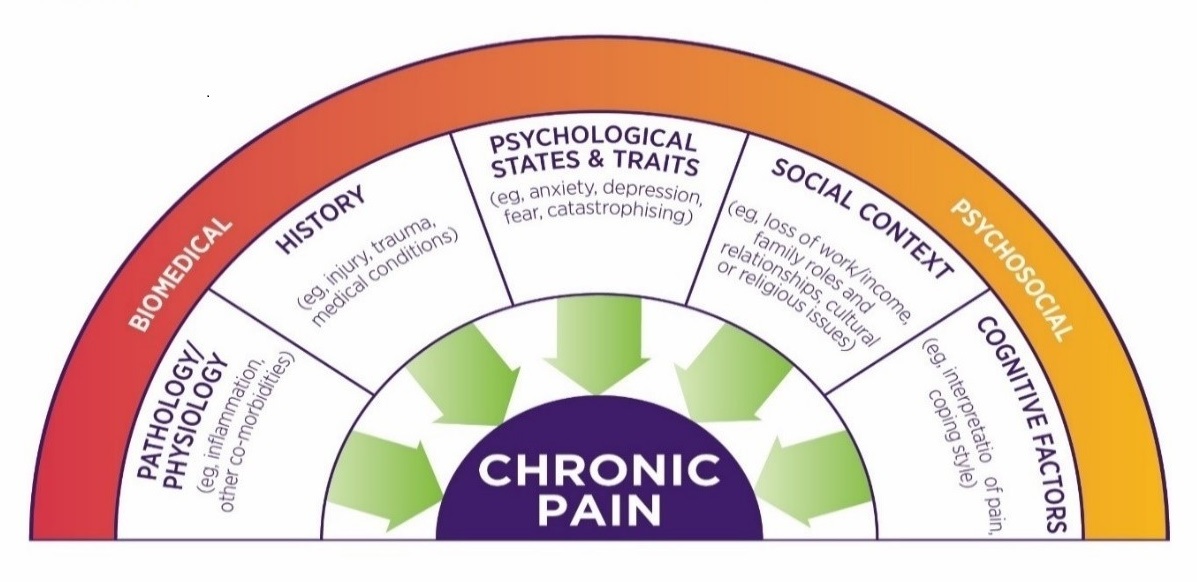

Once goals are agreed upon, a coordinated pain management plan can be formulated and, where possible, this should involve collaboration between primary care, specialists and allied health professionals. Multidisciplinary pain management addresses the different aspects of chronic pain, including the biopsychosocial impact on the individual (see Figure 1).10,11

The efficacy of a coordinated approach has been recognised to reduce pain severity, improve mood and overall quality of life, and increase function.10

Figure 1: Many factors contribute to an individual's experience of pain. Read an accessible text version of this graphic

In addition to improving physical function, a biopsychosocial treatment approach to chronic non-cancer pain helps patients understand and overcome secondary effects, including fear of movement, pain catastrophising, and anxiety, that contribute to pain and disability.10

It is important to acknowledge that multidisciplinary pain management planning may be a difficult concept for some people, particularly if they are experiencing distress because of dealing with persistent pain, frustrated with having to attend multiple appointments and concerned about the financial impact of visiting several different providers.

Encouraging self-management

Studies have indicated that the best care for chronic pain involves self-management by the patient with the support of a multidisciplinary team.12-15

This may include adhering to a prescribed medicine regimen, identifying their own treatment goals, and then working to achieve those goals.15

There is good evidence that while a large proportion of people with chronic pain are capable of developing and effectively employing their own self-management strategies – such as goal setting, thought challenging and activity pacing – many will need help acquiring these skills.15

The strongest evidence for delivering training in pain self-management for those with chronic disabling pain comes from structured multidisciplinary programs using cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) methods.15 Timely access to multidisciplinary pain management programs can be a barrier due to location and wait times, so GPs should be prepared to provide initial evidence-based information and upskill their patients in pain self-management strategies where possible.

Optimising non-pharmacological therapies

Recent studies have found that, as a first-line treatment for patients with chronic non-cancer pain, non-pharmacological therapies may achieve similar degrees of improvement in pain and function to opioid therapy, but without the harms of opioid dependence, addiction and overdose.13

It is recommended that GPs and patients optimise non-pharmacological and non-opioid medicine therapy for chronic non-cancer pain within a biopsychosocial framework before considering opioids.13

Non-pharmacological therapies can include strategies described above, such as activity pacing and psychological therapies. They can also include education, structured exercise programs and sleep hygiene – with input where available from the wider health care team eg, nurse educator, physiotherapist, psychologist, occupational therapist, social worker, rehabilitation counsellor and dietitian.8 With many different providers involved, care can become fragmented, so communication is vital. Usually the GP coordinates referral to providers and oversees a targeted treatment plan using available local resources.

Cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT)

Cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) helps patients to modify their emotional and behavioural response to pain by challenging cognitive processes eg, thoughts, fears and catastrophising about the pain.4

CBT has shown small positive effects on disability associated with chronic pain, and is effective in altering mood and catastrophising outcomes, with some evidence that this is maintained at 6 months.16

Acceptance and mindfulness-based interventions

Acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) focuses on psychological flexibility as the ultimate treatment goal.17

In the context of chronic pain, being psychologically flexible means accepting painful sensations and the feelings and thoughts surrounding pain while focusing the attention on opportunities of the current situation rather than ruminating about the past or catastrophising about the future.17,18 The behavioural focus of ACT is on setting goals that are important and valuable, instead of focusing on pain control.18

Physical therapies and activity pacing

Physical therapies such as physiotherapy, occupational therapy, therapeutic exercise, and other movement modalities play a significant role in chronic pain management, and positive clinical outcomes are more likely if these therapies form part of a multidisciplinary treatment plan following a comprehensive assessment.10

A key feature of engaging in physical activity is known as activity pacing. Activity pacing is described in the literature as a coping strategy that involves activity behaviour that is goal-contingent rather than pain-contingent.19

Although chronic pain is a complex and challenging area to manage, GPs and patients should be aware that several effective non-pharmacological therapies are available to support them (see Table 1).

Table 1: Examples of non-pharmacological therapies for chronic non-cancer pain

| Active physical therapies and techniques2,5,10 |

|

| Psychological therapies2,5,10,16-18 |

|

| Other treatment options2,5,19-21 |

|

When things get hard

Referral to pain management services may be warranted if patients have been unable to achieve their functional goals, or they are not progressing as expected. This may occur when current pain management measures are not helping and the pain is interfering in daily activities, causing distress and affecting the patient’s mental health.22

Managing patients with complex issues

People with chronic non-cancer pain should be appropriately assessed to determine the complexity of their needs and risk of harm.23

The following scenarios are generally considered complex and may be indicated for specialist and multidisciplinary review:

- taking two or more psychoactive drugs in combination (eg, opioids, benzodiazepines, antipsychotics, antiepileptics, depressants)

- taking opioids together with benzodiazepines

- patients with serious mental illness comorbidities, or taking antipsychotic medicines

- mixing pharmaceutical opioids and illicit drugs

- discharged from other general practices due to problematic behaviour

- recent discharge from a correctional services facility

- signs of potential high-risk behaviours.

Some GPs will be confident managing patients with mental health and substance use comorbidities while others may wish to seek specialist support.23

People who are at higher risk of opioid misuse, or have more complex issues, may need to be jointly managed between primary care, pharmacists, drug and alcohol services, and specialist services (eg, mental health, pain or addiction specialists).23

The risk of harm from opioids increases for patients on high doses, patients with complex comorbidities and those who are co-prescribed benzodiazepines and other sedatives.24

Conclusion

Non-pharmacological therapies have the potential to improve outcomes for chronic pain and comorbidities and tend to be low risk.12

GPs and patients can work together to formulate a pain management plan which includes multimodal non-pharmacological approaches that can be implemented through patient self-management, supported by a trusting therapeutic relationship over multiple consultations.12

Useful links for your patients

- NPS MedicineWise, Chronic pain explained

- NPS MedicineWise, Opioid medicines and chronic non-cancer pain

- ACI NSW Pain management network, Pain management: For everyone

- ACI NSW Pain management network, Pain and thoughts. A video about how negative thoughts and stressful life situations can influence pain.

- Hunter New England Local Health District, Understanding pain in less than 5 minutes, and what to do about it! A video that summarises the difference between acute and chronic pain.

- Pain Australia, List of pain services in Australia

- PainHealth, Pacing and goal setting

Acknowledgements

Thanks to the experts who contributed to this Medicinewise News.

Dr Andrew Broad is a general practitioner working in a suburban practice in Melbourne, Victoria.

Toby Newton-John is an Associate Professor in Clinical Psychology at University of Technology, Sydney and senior clinical psychologist at the Northern Pain Centre, Sydney.

References

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Opioid harm in Australia and comparisons between Australia and Canada. Canberra: AIHW, 2018 (accessed 19 April 2019).

- NSW Therapeutic Advisory Group Inc. Preventing and managing problems with opioid prescribing for chronic non-cancer pain. Sydney: NSW TAG, 2015 (accessed 8 January 2019).

- Australian Medicines Handbook. Chronic pain. Adelaide: AMH Pty Ltd, 2019 (accessed 10 January 2019).

- Royal Australian College of General Practitioners. Prescribing drugs of dependence in general practice, Part C2: The role of opioids in pain management. East Melbourne: RACGP, 2017 (accessed 19 March 2019).

- Analgesic Expert Group. Therapeutic Guidelines: Analgesic. Version 6. West Melbourne: Therapeutic Guidelines Ltd, 2012 (accessed 10 January 2019).

- Chou R, Turner JA, Devine EB, et al. The effectiveness and risks of long-term opioid therapy for chronic pain: a systematic review for a National Institutes of Health Pathways to Prevention Workshop. Ann Intern Med 2015;162:276-86.

- Busse JW, Wang L, Kamaleldin M, et al. Opioids for chronic noncancer pain: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA 2018;320:2448-60.

- Faculty of Pain Medicine. Australian and New Zealand College of Anaesthetists. Recommendations regarding the use of opioid analgesics in patients with chronic non-cancer pain. PM01 2015. Melbourne: ANZCA, 2015 (accessed 14 March 2019).

- Baldini A, Von Korff M, Lin EH. A review of potential adverse effects of long-term opioid therapy: A practitioner's guide. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord 2012;14.

- Pain Management Best Practices Inter-Agency Task Force. Draft report on pain management best practices: updates, gaps, inconsistencies and recommendations. Washington DC, USA: US Department of Health and Human Services, 2018 (accessed 18 March 2019).

- Turk D, Wilson H, Cahana A. Treatment of chronic non-cancer pain. Lancet 2011;377:2226-35.

- Holliday S, Hayes C, Jones L, et al. Prescribing wellness: comprehensive pain management outside specialist services. Aust Prescr 2018;41:86-91.

- Busse JW, Craigie S, Juurlink DN, et al. Guideline for opioid therapy and chronic noncancer pain. CMAJ 2017;189:E659-E66.

- Finestone HM, Juurlink DN, Power B, et al. Opioid prescribing is a surrogate for inadequate pain management resources. Can Fam Physician 2016;62:465-8.

- Nicholas MK, Blyth FM. Are self-management strategies effective in chronic pain treatment? Pain Manag 2016;6:75-88.

- Williams AC, Eccleston C, Morley S. Psychological therapies for the management of chronic pain (excluding headache) in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012;11:CD007407.

- McCracken LM, Vowles KE. Acceptance and commitment therapy and mindfulness for chronic pain: model, process, and progress. Am Psychol 2014;69:178-87.

- Veehof MM, Trompetter HR, Bohlmeijer ET, et al. Acceptance- and mindfulness-based interventions for the treatment of chronic pain: a meta-analytic review. Cogn Behav Ther 2016;45:5-31.

- Nielson WR, Jensen MP, Karsdorp PA, et al. Activity pacing in chronic pain: concepts, evidence, and future directions. Clin J Pain 2013;29:461-8.

- painHealth. Pacing and goal setting. Government of Western Australia Department of Health, 2019 (accessed 12 August 2019).

- Zou L, Zhang Y, Yang L, et al. Are mindful exercises safe and beneficial for treating chronic lower back pain? A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Clin Med 2019;8.

- Nicholas MK. When to refer to a pain clinic. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 2004;18:613-29.

- Royal Australian College of General Practitioners. Prescribing drugs of dependence in general practice, Part A: Clinical governance framework. East Melbourne: RACGP, 2015 (accessed 10 January 2019).

- Royal Australian College of General Practitioners. Prescribing drugs of dependence in general practice, Part C1: Opioids. East Melbourne: RACGP, 2017 (accessed 19 December 2017).

- Dowell D, Haegerich TM, Chou R. CDC Guideline for prescribing opioids for chronic pain - United States, 2016. MMWR Recomm Rep 2016;65:1-49.